Lucy Stone: An Incredible Woman Denounced Misogyny, Defied Inequality, And Upheld Women’s Rights

Lucy Stone, a pioneering suffragist and abolitionist, devoted her life to fighting inequality on all fronts. She broke gender stereotypes when she famously wrote her marriage vows to reflect her egalitarian ideas and refused to accept her husband’s last name. She was the first woman in Massachusetts to receive a college education.

Stone, one of the nine children of Francis and Hannah Matthews Stone, was born on August 13, 1818, in a remote area of Massachusetts. Her parents were New England natives who worked as farmers. Her ancestor served as a Patriot leader in the American Revolution, and the first Stones came in 1635 in search of religious freedom. She adopted her father’s fervour for abolition of slavery and was brought up in the Congregational Church.

Stone, who was far smarter than her siblings, was upset by the inequality that promoted boys and men to pursue higher education while preventing women from doing so. She started working as a teacher at the age of sixteen in order to save money for education. She attended Mount Holyoke for a semester in 1839 but was compelled to return home because one of her sisters was ill. She then enrolled at Ohio’s Oberlin College in 1843. However, Stone was not allowed to pursue her interest in public speaking at even progressive Oberlin. She turned down the “honour” of writing a commencement speech that would be delivered by a man in 1847, the year she graduated.

When Lucy Stone was a student at Oberlin, she met William Lloyd Garrison and got interested in the abolitionist cause. The American Anti-Slavery Society hired her as a public speaker after hearing her speech from the altar of her brother’s church in Gardner, Massachusetts after she graduated from Oberlin. Lucy Stone became one of the first women to emerge from the conventional, off-stage “woman’s sphere” and onto the public stage.

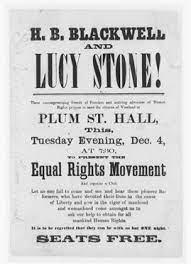

The first national women’s rights convention was organised in Worcester, Massachusetts, by Stone in 1850. Her remarks there were published again in the international press. Stone spoke at conferences across the US and Canada for five years. She kept going to the annual meetings for women’s rights and even presided over the seventh one.

In 1855, Stone married Henry Blackwell. The bride and groom announced that Stone would retain her own name in a statement that was read aloud by the minister during the wedding ceremony.

The statement said that current marriage laws “refuse to recognize the wife as an independent, rational being, while they confer on the husband an injurious and unnatural superiority, investing him with legal powers which no honorable man would exercise, and which no man should possess.”

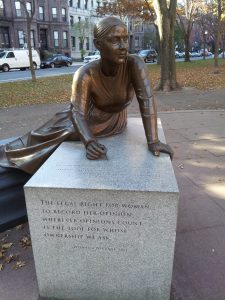

In 1858, Stone created yet another precedent by reminding Americans of the “no taxation without representation” principle. Her refusal to pay property taxes resulted in the impoundment and sale of the Stones’ personal belongings.

After the Civil War, Lucy Stone joined Frederick Douglass and others in supporting the Fifteenth Amendment as a partial victory in their fight for women’s rights. The passage of the Fifteenth Amendment outraged most women’s rights leaders because the right to vote was not guaranteed to women. This debate shattered the women’s rights movement. By 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and others had formed the National Woman Suffrage Association and were focusing their efforts on a federal woman’s suffrage amendment. Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe led the formation of the American Woman Suffrage Association, which chose to focus on state suffrage amendments.

By 1871, Stone had assisted in the organisation of The Woman’s Journal’s publication and was co-editing the newspaper with her husband Henry Blackwell.

In 1879, Stone registered to vote in Massachusetts, because the state permitted women’s suffrage in local elections, but she was removed from the rolls because she did not use her husband’s surname.

At the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, Stone delivered her final address before passing away later that year at the age of 75.

Lucy Stone was a “first” even in death. She chose the twelve pallbearers herself: six men and six women. In addition, she was the first person cremated in Massachusetts. However, her final intentions were disregarded by the cemetery where she is buried, Forest Hills, and her stone now bears the last name “Blackwell.”

Even though Lucy Stone did not live to see women win the right to vote, she played a crucial part in making it happen in 1920.

Also Read: La Mulâtresse Solitude: A symbol Of Slavery And Freedom